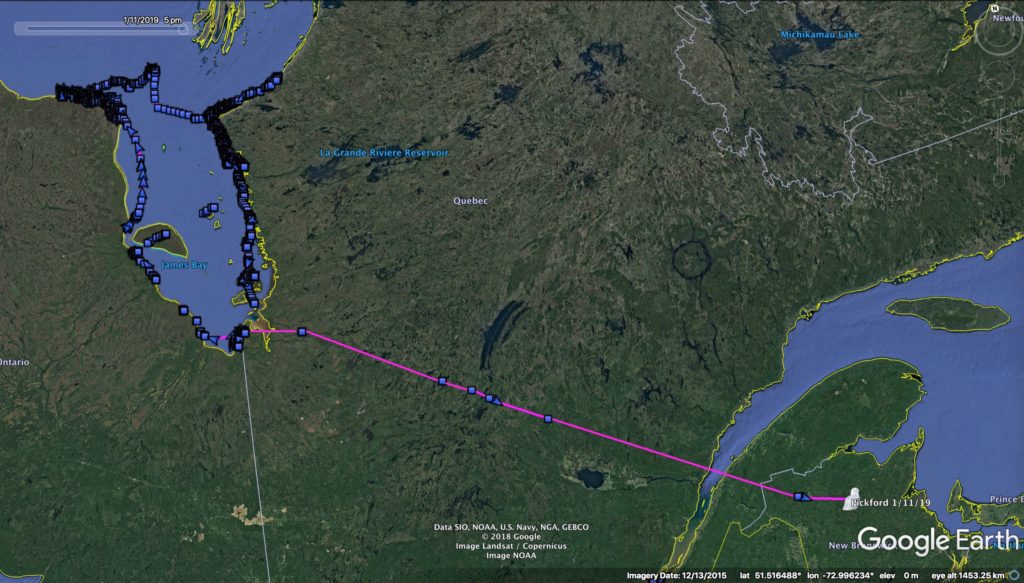

Pickford’s movements from the end of May until this past week, including her quick push across Quebec. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Pickford — a female we tagged last winter as a first-winter immature last season on the Upper Peninsula of Michigan — has been playing hide-and-seek with us for months.

The last time we heard from her in the spring was May 29, when she was heading north along the western shore of James Bay. Her transmitter connected with a cell tower at the isolated First Nations community of Attawapiskat, but we weren’t surprised that she dropped off the grid thereafter, since there are very few other cell stations in that part of the Canadian subarctic.

We got another ping from Pickford on Sept. 26, near another remote Native community on James Bay, this time on the eastern shore, and were hopeful that she was on her way south — but then we heard nothing more. The cell connection that time was poor, and we only got a small, teasing portion of her backlogged summer data.

So we were more than delighted Saturday night, Jan. 12, when Pickford phoned home — and unpacked nearly 11,000 GPS points that unscrolled her wanderings from the end of May until now. More surprisingly, she was calling from northern New Brunswick, having just made a rapid, long-distance flight from James Bay in only a couple of days.

The classic signature of an owl drifting around the subarctic waters on ice floes or icebergs. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

The story that those GPS points tell is a fascinating one (and all of her 2018-19 data is available for you to explore on her interactive map if you want to follow along). Pickford essentially circumnavigated James Bay over the summer and autumn — up to the junction with Hudson Bay, then out onto the bay itself, where we see the classic signature of an owl riding on ice floes or bergs: a very smooth, very slow, very consistent movement at about 0.9 km an hour (0.6 mph) as the wind and tide pushed her. She spent three days out on Hudson Bay, then flew to its eastern shore. She spent the remainder of July, August and most of September wandering around the Hudson/James bay junction, then Sept. 24 began moving south. She looped around the southern end of James Bay and started back up the western shore again.

Pickford spent the months of November and December back in almost the same place where she had paused in May, south of Attawapiskat on the western coast, either not quite close enough to the village to grab a cell signal, or without sufficient battery power to transmit, because of the short days and low solar angle. On New Year’s Eve she started moving once more, flying east across Akimiski Island and another 125 km (78 miles) to the eastern coast of the bay.

This time, she hugged the coast until Jan. 5, then for reasons known only to her, Pickford struck out southeast, away from the bay and into the spruce forests of Quebec. Over Jan. 10-11 she flew hundreds of kilometers in a hurry, crossing the St. Lawrence into northcentral New Brunswick’s Northumberland County. Her location was about halfway between Mount Carleton Provincial Park to the west, and the former Heath Steele Mines to the east. Cellular maps show a single tower about 30 km (18 miles) to the north, along Rte. 180 — not much, but apparently just enough.

Once again, we saw the advantage of new software from CTT that permits the transmitters to send a huge chunk of data at once. In previous years, we would only have gotten a few hundred data points per transmission, and it sometimes took weeks to get all the backlogged GPS points — assuming the owl stayed close to a cell tower. Now the unit hangs on to the cell signal until the data are all sent, but that also drains the battery, so it may be a little while before we hear from Pickford again — if she’s somewhere close to a tower, of course.

* * * * *

What about the other owls? Not a lot of changes to report. Coddington, the newest bird, is moving around a 4,700-acre (1,900 ha) area of the northern Buena Vista grasslands and adjacent ag lands south of the town of Plover, Wisconsin, where he was trapped. Farther west, Woodworth remains south of the Turtle Mountain plateau on the North Dakota/Manitoba border, where he’s been after moving 240 miles (390 km) north of his trapping location. And in Saskatchewan, Pettibone shifted north a bit to near the town of Aylesbury, west of Alexandra Lake, 195 km (121 miles) northwest of Regina.

We’ve not heard from Wells since New Year’s, and Island Beach (who has fans who keep asking about him) since he checked in last November from east-central Quebec, where we’re amazed he found a cell tower.

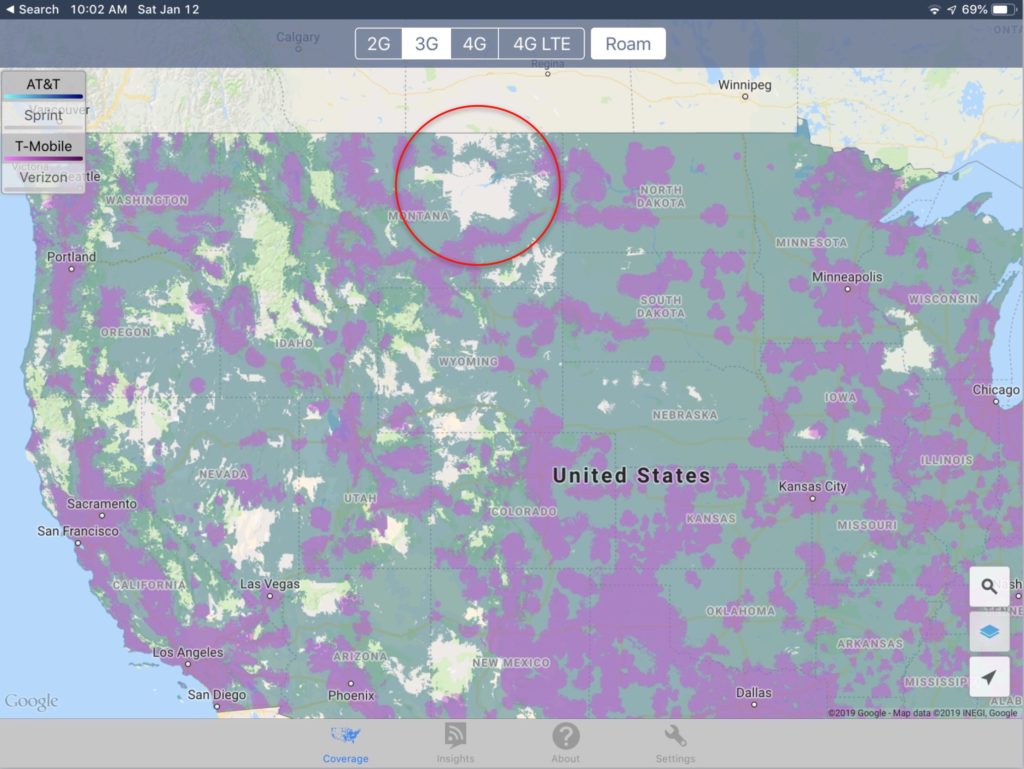

The big empty (at least from a cell service perspective) in northeastern Montana. (Image from CellMaps app)

A lack of cell coverage may also explain why we haven’t heard from Stella since she moved south through Saskatchewan. Her last transmission was Nov. 23, just a few kilometers from the Montana border. If she kept moving south, as seems likely, she would have entered one of the largest holes in cell coverage in the Lower 48. This is an area that includes the 2-million-acre Fort Peck Indian Reservation and 900,000-acre Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge, among other holdings. It’s spectacular, wildlife-rich country — but as the map above of U.S. cell service shows, it’s a whole lot of empty when it comes to cell service. Fortunately, if and when she heads north again she’ll pass through Saskatchewan, which has a very dense cell network.

3 Comments on “Pickford Phones Home”

Your stories are like reading a good mystery. Love hearing your project snowstorm updates.

If only these beautiful birds could tell us why they fly where they do!! They seem to be free spirits. Love to hear your updates.

I enjoy reading these articles along with the tracking it’s amazing! Thank you.