In the last light of sunset, Stella lands on a utility pole on Amherst Island, ready to start her evening hunt. (©Dan Lafortune)

It’s been quite a week since the last update. The low point, obviously, was confirming Hereford’s death, but there’s also been a lot of very cool news from the other owls, and that’s what we’ll focus on this time. We won’t hit every owl (like Stella, whose great photo our friend Dan Lafortune got on Amherst Island recently) but check the maps for updates at least twice a week.

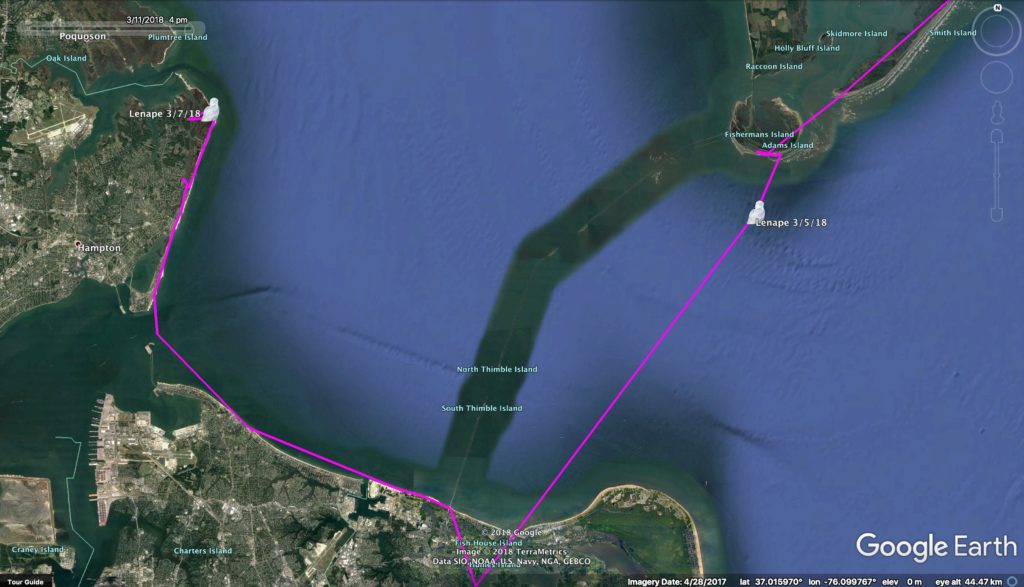

Why take the bridge when you can fly? Lenape made a 14-mile crossing of the Chesapeake Bay last week, just east of the immense Bay Bridge-Tunnel. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Where to start? Maybe with Lenape, another of the New Jersey snowies — though he’s “New Jersey” in name only these days, since this young male has been wandering up and down the mid-Atlantic coast all winter. He’s been down on the Eastern Shore for the past few weeks, but even so, we were surprised to see him head all the way to the southern tip at Kiptopeke last week — and then launch himself 14 miles (22.5 km) across the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay just after dusk on March 5! He flew about 34 mph (564 kph) and made landfall at Lynnhaven Inlet, near First Landing State Park in Virginia. Then he turned north, crossing the mouth of the James River to Plum Tree NWR near Langley Air Force Base. If he’d turned south, though, he would have been only 25 miles (40 km) from becoming our first tagged owl in North Carolina. And I wouldn’t bet against it happening.

Speaking of big movements, both Arlington in Wisconsin and Ashtabula in North Dakota have been moving north…ish. Arlington, who made two big loop flights earlier in the winter only to end up where he started, moved 106 miles (173 km) straight-line distance in the past week or so, and is now near Alma Center southeast of Eu Claire, WI. Along the way, he past just a few miles south of Austin, Straubel and Bancroft in the Buena Vista grasslands.

Tom Koch got this great photo of Bancroft, who is finding his neighborhood in central Wisconsin a little more crowded these days. (©Tom Koch.)

Ashtabula flew a wide curve tracing 95 miles (154 km) to the north, west and then south, but was only 30 miles (49 km) from where he started. As we’ve discussed before, this is typical late winter/early spring restlessness.

The ice is going fast on Lake Erie, but Hilton only came ashore briefly last week before heading back out — the ice margin is a rich hunting ground for waterfowl. (NOAA CoastWatch)

It’s been a while since we’ve heard from Hilton, but she reappeared last week just east of Erie, Pennsylvania, having spent recent weeks out on the fast-receding ice of Lake Erie, which now covers only about a quarter or less of the lake. Then she headed right back out onto the ice again.

Up in southern Canada, Hardscrabble has moved back northwest to his 2016-17 territory near Cobden. Dave Okines from Prince Edward Point Bird Observatory has made several attempts to recapture him this winter, since his three-year-old transmitter — while charging beautifully — has a glitchy battery that browns out after a few seconds every time it transmits. We get a current location, and anywhere from 20 to 100 of his backlogged points from last winter — which isn’t enough to catch him up to date, since there are probably 14,000 or so points in there. Now that he’s moving around much more widely, it may be impossible to get him again this winter. Wells and Chickatawbut are having no such problems, and remain where they’ve been all winter in southern Quebec.

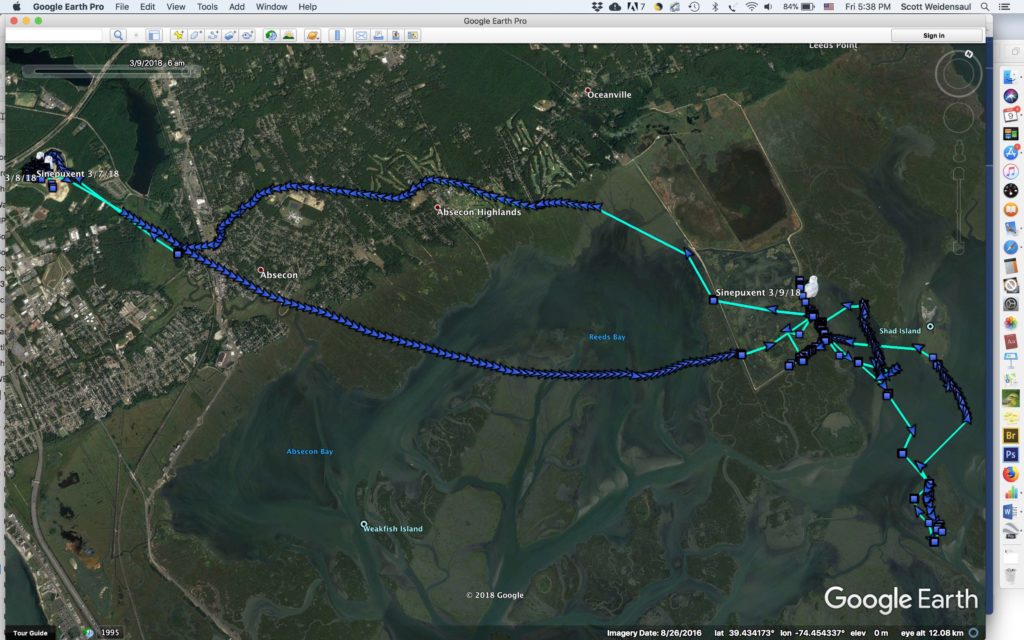

Recording data every six seconds when she’s in motion, Sinepuxent’s transmitter traces every twitch of her flight inland and back to the New Jersey coast. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Finally, Sinepuxent is providing us with an incredibly detailed look at her movements. We have an experimentally more powerful transmitter on her, a bit bigger than usual (and only appropriate in this case because she’s a very large owl). With its heavier-duty solar capacity, coupled with longer days and higher solar angle providing more power, we have switched her unit to “flight mode,” which uses the onboard accelerometer to detect motion and immediately begin collecting GPS data every six seconds. That means we can watch literally almost every twist and turn (complete with flight speed and altitude data) as she flies — and she did some flying this past week.

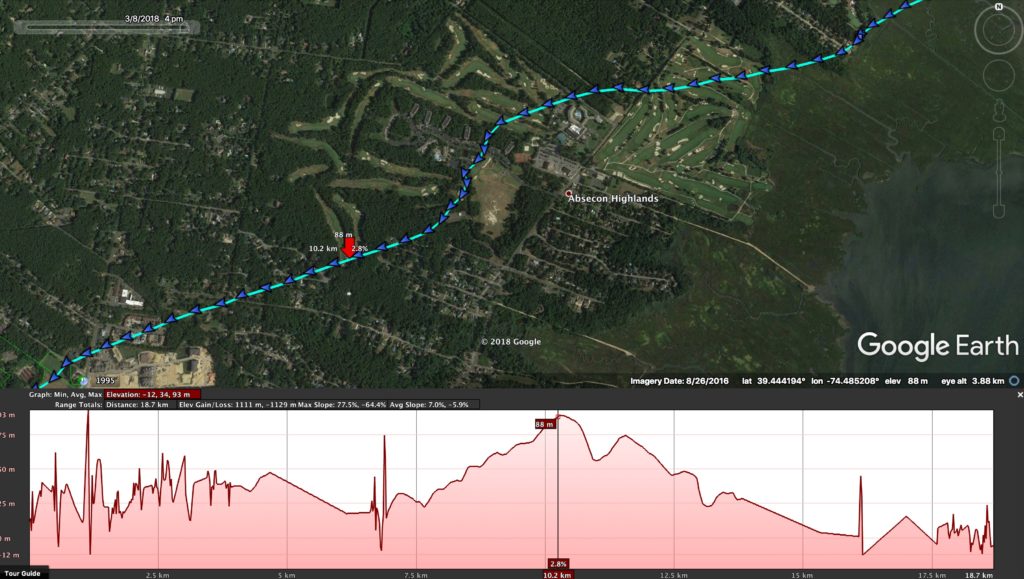

An elevation view shows how Sinepuxent steadily gained altitude to about 300 feet (90 m) and then glided down on her inland flight. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Since the end of February she’d been hanging around the Brigantine unit of Forsythe NWR north of Atlantic City, NJ, where she’s been photographed with several other snowies along the refuge’s popular wildlife drive. But on March 7, just after we switched to flight mode, Sinepuxent took off and made a roughly 30-minute flight inland, which her data captured in incredible detail. We can see her coming in low off the salt marsh, gaining altitude as she crosses the shore and reaching a peak of about 300 feet (90 m) as she passes Absecon Heights. Then she glides down, landing for a couple of hours along the edge of a tidal creek in the middle of the night before making another quick flight to landfill along the Garden State Parkway, where she spent the next day and a half. Mike Lanzone from CTT noted that when she’s coming in for a landing she often rises high, then parachutes straight down — possibly a behavior allowing her to scan the surroundings for predators before perching.

Landfills — especially those that are capped and covered in grass — are magnets for raptors, since they have a lot of small mammals. They are also dangerous, because many landfills flare off excess methane from vent pipes, which look like innocuous perches for a hungry hawk or owl, but which can suddenly erupt in a geyser of flame; a lot of raptors are killed or injured by such flares every year, their feathers sometimes scorched away to the quills. On the other hand, Sinepuxent could have continued a few more miles to the Atlantic City International Airport, which would hold its own dangers.

Twists and snap turns probably show Sinepuxent going to prey — likely ducks or gulls — out over the water. (©Project SNOWstorm and Google Earth)

Instead, a dusk on March 8 she turned around and flew back to Brigantine, and flight mode has since recorded her making what look like periodic hunting flights out over the marshes around the auto tour, where she was posing for more pictures this weekend.

5 Comments on “Across the Bay and Off the Ice”

I saw a snowy owl in south holland Michigan tonight-do they live around here typically?

This has been a great winter for snowy owls in Michigan and the rest of the upper Midwest and Great Lakes. A few come down almost every winter, but periodically we’ll get a large influx into particular regions, usually as the result of a productive breeding season the previous summer in the Arctic. They’ll start heading back north within the next month, so enjoy them while you can.

Thank you-I will

I’m obsessed …. I look at the pics every few hours on EBird . Today there is photos of a deceased Snowy due to barb wire and it has got me wondering and worrying about all owls but one in particular . The Snowy that has been seen all the way south in Ector Texas …. it’s almost April and it is still there ! Will it travel north on its own or does it need a ride ? I’m so worried ……

Every time there’s a big irruption, like this year’s in the Northeast, Midwest and Plains, there are a few individuals that go farther than normal — sometimes a lot farther. (The record was probably the snowy owl that showed up in Hawaii a few years ago.) The trigger for migratory birds to move is usually a combination of weather and day length, along with their internal clock. Most snowy owls will be heading north in the coming weeks, with adults usually moving north earlier and juveniles (which are too young to have to worry about finding a mate and setting up a territory) migrating somewhat later. When and whether a bird can migrate is also going to depend on its physical condition, and those that have been compromised by illness, parasites or injury may simply not be able to. But assuming the Texas bird is healthy, there’s no reason it won’t start heading north on schedule, like those wintering in more traditional regions.